I created an Excel year calendar recently. Here's a link to it. It's completely dynamic, allowing you to show the calendar for any year between 1900 and 9999. The only user interaction is to enter the year. The rest of the calendar updates automatically.

Below is the logic I used.

The first thing to do was to work out the day of the week on which 1 January fell. So I concatenated the year on to the string "01/01/" and the value from concatenated the year on to "01/01/", and calculated its weekday from there.

=VALUE("01/01/"&A1)

The ampersand is a shorthand route to accomplish the CONCATENATE function. =A1&A2 simply butts the contents of A1 up to the contents of A2. The VALUE function tries to interpret the text that results from the CONCATENATE function as a value. It sees it as a date, and so stores that date in the cell.

To calculate the day of the week of that date, I used the WEEKDAY function.

=WEEKDAY(B1,2)

This returns a serial number between 1 and 7, 1 meaning Monday, 2 Tuesday through to 7 Sunday. The "2" at the end of the formula determines how to return the weekday. I always use 2, as I always think of Monday being the first day of the week. But you could use 1 to allow your week to start on a Sunday; of 3 if you'd prefer 0–6 instead of 1–7.

Next, I created a table showing each of the months' lengths. Eleven of them hardcoded, as they're the same length every year. February’s entry used the slightly cumbersome formula for working out whether a year leaps. Years divisible by 400 are leap years; those divisible by 100 are not; those divisible by 4 are; all others are not. In that order. The formula for determining whether a year is a leap year is as follows:

=IF(MOD(A1,400)=0,"Yes",IF(MOD(A1,100)=0,"No",IF(MOD(A1,4)=0,"Yes","No")))

The results of that were used to determine whether to populate the number of days in February with a 28 or a 29.

=IF(B4="Yes",29,28)

I completed the table with the following columns: first day of the month (as a serial number again), last day of the month, and the last day of the previous month. This used similar concatenation logic to that described above—creating a date text string, interpreting this as a value and calculating its weekday.

That was all the data I needed to drive the calendar, and I put it all on a working sheet. The visual calendar was placed on a separate sheet, headed with the year that drove some of the formulae described above.

On the calendar sheet, the first row of January’s dates was created by comparing the number of the day of the week each cell represented with the day the month started on to establish whether to show a blank (the month hasn’t yet started) or a number—either a 1 for the first day, or the previous cell plus 1 for subsequent days.

The subsequent rows’ entries simply compare the previous day with the number of days in that month. If the two are equal, then that and subsequent entries display blanks; if not, then we simply increment the previous entry by one.

Each month has six rows of entries to accommodate the rare months that start late in the week and drip a day or two into week six—January 1900 being a good example, starting on a Sunday.

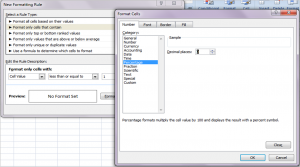

Once the numbers are in place, the remainder of the look and feel is accomplished through conditional formats. Blank cells have no borders; those representing weekends are shaded with borders; those representing weekdays are clear with borders.

Combining so many beautiful elements of Excel into a spreadsheet so useful was rewarding to say the least. I hope you enjoy the logic and can find a use for the calendar.

Trouble with formulae? Lookups not going so well? The Wizard of Excel can help. Dan Harrison offers practical tips and examples, as well as Excel training and consulting.

Trouble with formulae? Lookups not going so well? The Wizard of Excel can help. Dan Harrison offers practical tips and examples, as well as Excel training and consulting.