There are two big problems with most risks and issues registers:

- They’re difficult to read

- They’re difficult to maintain.

Let’s start with the readability. Usually, they’re a lifeless grid in a tiny font with lots of columns and, depending on your project/programme, lots of rows. There is nothing to distinguish between the rows other than the contents of the eight-point type in each of the cells. Risk or issue titles are unnecessarily verbose, and it’s often not clear what an item represents by reading it.

To solve this problem, I think it's useful to include a "Headline" column in 14-point bold. Maximum of ten words to give a high-level description of what the entry is all about. People will read it and say “Ah, yes. I know that one”.

Next, make sure all of the columns are absolutely necessary. Nugatory columns are a pain to fill in, and deflect from the important columns when viewed.

Use 90° text alignment for the short fields (such as who raised it and who it's assigned to) to save width for the columns containing important textual information.

Now some pointers to make your registers more manageable.

Don’t hive off closed items. Just close them in the status field. It’s important that you keep them for posterity and completeness. Use Excel’s Custom Views to make sure you don’t see them when you don't need to. Keeping data in a single location is important in Excel, partly to make your spreadsheets easy to use, but also to ensure that they're easy to analyse.

Have a single register to house both risks and issues. This is a biggie that I can’t stress enough. Although some of the columns for each register are subtly different, there are quite a few that are consistent between the two. Keep two registers and your reference numbers get cumbersome, and cutting and pasting from one to another when risks become issues is a pain.

If a column for risks is sufficiently similar in nature to an issues column, then combine the two. If needs be, have three heading rows, one for risks, one for issues and one for a combined view, and use Custom Views to hide the two title rows that are redundant for a particular view. If you’re showing risks, hide the issues and combined titles, for example.

If columns are being used to determine the Custom View via filtering (e.g. Status: Open; Type: Risk), then hide these two columns in that view—they’re redundant. Instead, include a cell above the title row saying “Open risks” that can be displayed for that view. For each view, have a dedicated row above the title rows purely for this function, summarising the view. This can be printed on every sheet through repeated titles. And if you want, you can succeed it with the number of records in the filter.

And below are a few other points worth making.

Unless you’re using some shared web interface, use Excel. Don’t consider anything else. Excel is perfect for data like this. Word is appalling; PowerPoint worse.

For the risk or issue titles, word your items as statements of fact. Risks should be phrased as if they’ve happened. Issues similarly, because they have. “There is no environment available for performance testing”, for example, is the wording whether it's a risk or an issue.

Keep update summaries brief, and archive old updates into a separate, hidden column in four-point. This is for audit purposes and is rarely referenced. Its font can be increased as and when you need to read it.

By combining your risks and issues, you can have generic reference numbers that support both, ones that never need to change.

Build Custom Views for: open risks; open issues; open items; all items. You can add more complex views if necessary, such as: imminent risks; high-impact issues; escalated items.

Use conditional formatting to work out how to colour items, but only colour the rating cell and make it narrow. Colouring the entire row makes it difficult to read and draws the eye too much.

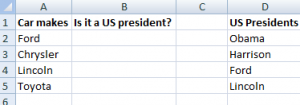

Here's an example.

Trouble with formulae? Lookups not going so well? The Wizard of Excel can help. Dan Harrison offers practical tips and examples, as well as Excel training and consulting.

Trouble with formulae? Lookups not going so well? The Wizard of Excel can help. Dan Harrison offers practical tips and examples, as well as Excel training and consulting.